It’s a strange and unfortunate truth that the action genre is habitually relegated to the league of second-tier cinema by many of the most serious-minded western critics and film fans. Perhaps it would be a different story if Hollywood orchestrated their blockbuster spectacles with the same level of inventive intricacy and rhythmic grace as the best action films from Hong Kong, a territory whose most talented filmmakers have long displayed a keen awareness of the uniquely cinematic manipulation of visual space and movement that defines the action genre.

In the greatest Hong Kong action cinema, plot is always a secondary concern at best, and is often treated as burdensome weight to be kept to a minimum. Here the phrase ‘style over substance’ feels obsolete, since these are films where the two are frequently inseparable – and to distinguish ‘art’ from ‘entertainment’ feels even more redundant.

With such a rich and lengthy history to draw from, any list of the best Hong Kong action films will inevitably come with its controversies (many will be aghast at this Top 10’s lack of Bruce Lee and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon) so the ten featured here should be taken as nothing more than a pick of personal favourites from a region that spent decades at the forefront of action cinema.

Honourable Mentions:

Come Drink with Me (1966, dir. King Hu), Fist of Fury (1972, dir. Lo Wei), The 36th Chamber of Shaolin (1978, dir. Lau Kar-leung), Drunken Master (1978, dir. Yuen Woo-ping), Police Story (1985, dir. Jackie Chan), Peking Opera Blues (1986, dir. Tsui Hark), Bullet in the Head (1990, dir. John Woo), Iron Monkey (1993, dir. Yuen Woo-ping), Fist of Legend (1994, dir. Gordon Chan), Exiled (2006, dir. Johnnie To)

10. The Legend of Drunken Master (1994, dir. Lau Kar-leung)

Project A and Police Story have the more impressive stunts, but while those and other Jackie Chan vehicles can often come across as half-formed – like a series of excellent set pieces with the mere skeleton of a film around them – this cheeky take on Cantonese folk hero Wong Fei-hung lands on the top of the Chan heap as the most well-rounded, consistently enjoyable film from one of cinema’s great physical performers.

Under the guidance of Shaw Brothers veteran Lau Kar-leung, The Legend of Drunken Master (aka Drunken Master II, though it’s more a reboot than a sequel to the 1978 original) integrates its slapstick spectacle into a relatively fleshed out reality of colourful sets, colonial oppressors and strained family relations. Better yet, this is that rare case of a Hong Kong-based Jackie Chan film in which another actor frequently manages to steal the spotlight, that actor being a comedically gifted Anita Mui as Wong’s delightfully outspoken stepmother.

That being said, the main draw is inevitably Chan himself, who slides, staggers and gyrates his way through some of the finest martial arts choreography put to film. The drunken master’s dependence on hazardous levels of alcohol to unlock his full potential as a fighter functions as a compelling (and likely unintentional) metaphor for the danger Chan is willing to put himself and his body in for the sake of entertainment – and entertain he most certainly does. Through the stunning fluidity of his inebriated combat, Chan makes an enthralling case for himself as the Gene Kelly of action cinema.

9. Kung Fu Hustle (2004, dir. Stephen Chow)

Lampooning the martial arts genre with Mel Brooks levels of wit and affection, Stephen Chow’s Kung Fu Hustle channels classic Looney Tunes as it pushes the most familiar ingredients of kung fu cinema to their logical extremes, or deflates them completely. It’s a shamelessly hyperbolic work of artful silliness that beats contemporary actioners of the East and West at their own game by refusing to take itself the slightest bit seriously.

The plot’s linear trend is set from the opening minutes, in which the local police force is beaten up by some small time gangsters who are quickly massacred in turn by the meaner Axe Gang. Kung Fu Hustle ditches all pretences of honour and spirituality in lieu of a simple narrative food chain of big fish getting eaten by even bigger fish until the final, ludicrous clash between two kung fu demigods: one a balding creep wearing sandals and a wife-beater; the other a lowlife schmuck who first learned martial arts from an overpriced pamphlet.

Along the way, Chow continues to exhibit his remarkable flair for visual comedy that relishes in the suffering and misfortune of his characters, while littering his cruel slapstick with tongue-in-cheek homages to Hollywood cinema, from Tim Burton’s Batman to the classic Astaire-Rogers musical Top Hat. After an hour and a half of delirious conflict escalating beyond any imagined limits, the film’s surprisingly touching final display of childhood innocence is a pitch-perfect encapsulation of its director and star’s sensibilities: in the medium of cinema, Stephen Chow is indeed a kid in a candy shop. May he never grow up.

8. A Better Tomorrow (1986, dir. John Woo)

John Woo’s best films succeed as art because they’re not afraid of being called trash. Where many of his Hollywood action contemporaries would either keep their mayhem on a leash in some half-hearted attempt at ‘respectability’ or try to preempt all mockery with a layer of jokey self-awareness, Woo goes all the way, pushing his tough-but-sensitive male leads into the most overblown of conflicts in which shoot-outs and pyrotechnics are matters of the heart.

It is with A Better Tomorrow that the legendary director began establishing himself as cinema’s premier craftsman of what could appropriately be called ‘dick flicks’: cinematic Trojan horses that use explosive set pieces and tough-guy characterisations to convey the most intense of bromantic man-feels. Though Woo’s style would become more refined in the coming years, it would also scale new heights of outrageousness, positioning this Triad soap opera of loyalty in a changing world as a relatively grounded entry point for the director’s distinct brand of brutal screen poetry.

In the film’s central brotherly love triangle between two Triad members and a cop, it is the swaggering gangster Mark who dominates the spotlight, with Chow Yun-fat delivering perhaps the most charismatic performance of his career. He earns his place among the great action heroes of cinema in his first, bloody confrontation with a Taiwanese gang, and then breaks our hearts when we see the price of this conflict.

But it’s through the relationship between its three main men that A Better Tomorrow really pulls us through the wringer. Many of the film’s best scenes are those that either tap into the despair of seeing an old friend privately suffering, or channel the shared regrets and resentments of its characters into some comradely and cathartic sequences of bullet ballet. Sure, the Woo equation for manly expression is not without its limitations (he never really did figure out how to articulate affection beyond the male-male kind) but it’s easy to picture our world as a more emotionally healthy place if more of our entertainment pulled off such a passionate and rousing combination of testosterone and tears.

7. The Grandmaster (2013, dir. Wong Kar-wai)

Some will cry blasphemy upon seeing how this relatively late entry in the recent wave of films mythologizing the life of Wing Chun master Ip Man is ranked above an established classic like A Better Tomorrow (not to mention the many beloved martial arts flicks that didn’t even make the list). But give it time and the consensus may catch up with this aesthetically impeccable blending of history, fantasy and personal melancholy from Hong Kong’s greatest director.

After dipping the occasional toe into action cinema with vibrant achievements like 1994’s Ashes of Time and 1995’s Fallen Angels, The Grandmaster finally sees Wong Kar-wai undergo a full genre immersion, presenting a richly disorienting saga that revels joyously in the stylistically supercharged spectacle of its balletic fights. It seems only natural, given the man at the helm, that every frame bursts with life and colour, from its luxuriant interiors to its expansive snowscapes. But once more, Wong doesn’t let us down on the thematic and psychological fronts either, basing his sumptuous visuals around the calcifying effects that time has on the film’s real main character: the hopelessly vengeance-driven Gong Er.

Like Ashes of Time and 2046 before it, The Grandmaster observes the degradation of a soul that’s tragically stuck in a long-gone moment, the memory only growing larger as the years pass. It is through the grandmaster Ip Man himself that the film finds hope, exemplifying the persistence and plasticity necessary in navigating a tumultuous life of changing fortunes and severed ties. While Gong sorrowfully shrinks into herself, Ip remains open, finding therapeutic meaning in honing his art and sharing it with the world.

In short, Wong brings us yet another achingly seductive sensory poem of enduring heartbreak and emotional displacement, only this time with some pretty cool scenes of Tony Leung and Zhang Ziyi hitting people.

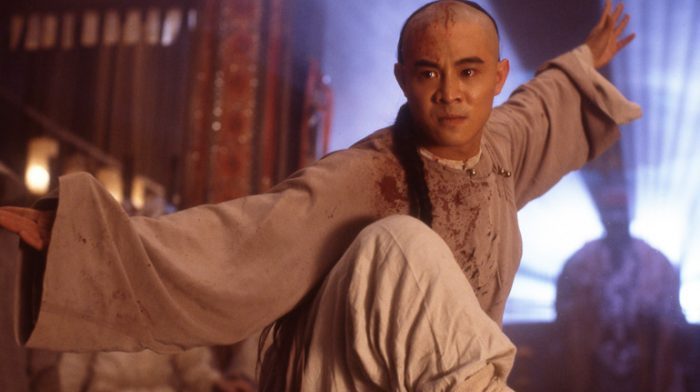

6. Once Upon a Time in China II (1992, dir. Tsui Hark)

In the hands of Jet Li and Tsui Hark, the much-mythologised Wong Fei-hung is a very human folk hero adapting to a changing China and its incoming western influence. This took the form of distractingly heavy-handed nationalism in 1991’s messy but endearing Once Upon a Time in China, in which the Hung Ga expert ousted the foreign devils who sought to enslave his people.

The tauter, slightly more thematically nuanced sequel offers a flipside in the form of the White Lotus Sect, a fanatically xenophobic and wondrously theatrical cult that suggests a dark perversion of the love of cultural heritage that flows through the arteries of this series. But even these misguided and brainwashed evildoers draw more sympathy than the devious military authorities who take advantage of such extremist outliers as a means of ruthlessly clamping down on anti-imperialist dissidents.

Tsui uses this politically resonant setup as the foundation for what just might be his finest and most cohesive series of spectacles to date. Amidst some complex and creative choreography (there’s a good chance Yuen Woo-ping is the reason you first became a martial arts film fan), Tsui’s exuberant direction soars off a passion for the medium as glorious sparks fly in the meeting between classes, comrades, cultures and genders.

When one character brings a 19th century camera to the action, it’s easy to see why the White Lotus Sect – a group that establishes the fake divinity of its leader via flashy deception – feels so threatened. Not even this spectacularly showy cult can compete with the magic and illusion that this tool will one day bring, especially when the person behind it is as fervent and talented a showman as Tsui Hark.

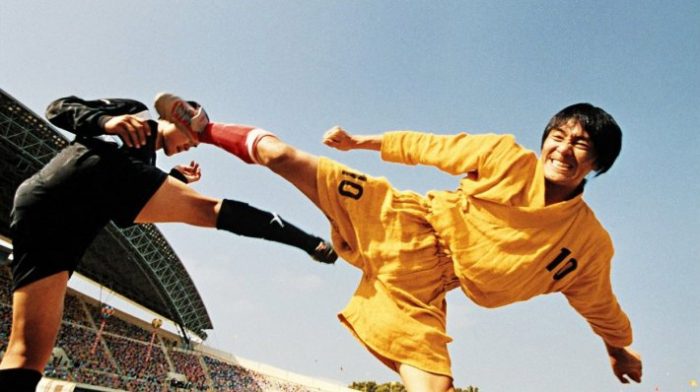

5. Shaolin Soccer (2001, dir. Stephen Chow)

Stephen Chow is a cinematic master who lends his immense abilities to the cause of taking the piss. The irreverent Shaolin Soccer, for instance, manages to enter the category of ‘action film’ by inflating the long-recycled tropes of formulaic sports dramas into the absurd stuff of comic books. The football (if I may be so British) is rendered an airborne instrument of destruction to be used by whoever can master it best. The film is probably a more realistic portrayal of kung fu than soccer – and it’s nowhere close to a realistic portrayal of kung fu.

Likewise, every narrative beat that the hack filmmaker’s manual dictates should be awash with cheap sentiment is gleefully undermined amidst a seamlessly woven stream of sight gags delivered at a rate that would make peak Zucker, Abrahams and Zucker proud while leaving your inner 10-year-old in a state of anarchic bliss. There may not be another comedy from this century that’s so dense with jokes while still maintaining this strong a hit-to-miss ratio.

So completely does Shaolin Soccer embody its silly sensibilities that its manic action at times achieves a strange and fantastical beauty that leaves us sincerely moved by such ridiculous sights as a middle-aged man being pummelled half-dead with a flaming football. In the film’s colossal final game, it makes perfect sense that Chow would choose the last team standing between our heroes and victory to be a group of soulless Ubermenschen clinically nurtured with the money of a corrupt businessman. To a man who imbues his work with such childlike energy, imagination and cheek, what could be more frightening than these cynical creations?

4. Running Out of Time (1999, dir. Johnnie To)

Like Howard Hawks in full auteur mode, Johnnie To immerses us in the world of men for whom ‘the job’ is everything – their source of pride, income, companionship, adventure and even romance. At his best, To himself approaches his filmmaking with similar efficiency and the results are immaculate feats of craftsmanship like Running Out of Time, a film in which intricate setpieces of deception and one-upmanship are to Johnnie To what water is to a fish.

A rare work in which everything flows seamlessly, Running Out of Time thrives on making disparate parts feel inseparable: cops and criminals are kindred spirits, work is play, style is substance, high drama is humorous, and truly being alive means knowing that you’re going to die. The action never flags because the film’s dazzling effect stems not from testosterone-infused bluster but from cunning ideas that compose an elaborate game of cat and mouse, charging a variety of props, words and architectural features with dramatic significance.

For a Johnnie To action film, Running Out of Time has an unusually low body count but mortality is clearly in the forefront of the mind of Cheung, a man whose terminal illness puts him on the brink of oblivion as he readies himself for one last burst of life. Cheung’s eleventh-hour seizing of his own destiny comes at the expense of Inspector Ho’s grasp of his own destiny, but maybe that’s not such a bad thing either. On one level, this is a film about control – about learning to take it, and also learning to lose it.

As Ho surrenders himself to the elements beyond his control and learns to trust in Cheung’s flamboyant and mischievous methods, Running Out of Time manifests as an ode to the city. That’s not any city in particular but ‘the city’ as an ideal and an essence – a mysterious and invigorating spirit that runs through every vibrant metropolis where the daring and the dedicated live their fleeting existences to the fullest.

3. Hard Boiled (1992, dir. John Woo)

Though those big, manly tears initiated by Woo’s previous classics aren’t as plentiful and bittersweet this time around, Hard Boiled still feels like the moment where the director’s unique and intricate style reached its nirvana state before Hollywood snatched him up and derailed the creative development of one of the great genre filmmakers of recent decades.

If The Killer was action cinema as impassioned, late-night pop ballad, Hard Boiled is John Woo’s jazz number. Thin on plot even by this director’s standards, the film is a playfully virtuosic work that moves with an unconventional rhythm between high-octane setpieces of gunplay and deception that are held together by the durable bonds of its male characters.

It is here that Woo comes closest to doing for violence what so many arthouse directors have tried to do for sex: make it a channel for all forms of interpersonal emotions, be it hatred, respect, compassion, love or even lust – check the coded homoeroticism woven into the film’s undercover cop drama.

Building up to one of the most deliriously excessive and boldly orchestrated third acts in action cinema history, Hard Boiled is the John Woo experience at its most unrefined and unbounded; the work of a master entertainer with enough confidence in his craft to simply flex his filmmaking muscles for over two hours.

2. The Mission (1999, dir. Johnnie To)

Every scene is an action scene in Johnnie To’s The Mission, even the ones where its hardened gangsters are just sitting around doing nothing. In one of the most impeccably crafted films of the ‘90s, there is nary a second that isn’t charged with tense significance and To’s signature post-modern cool. The director is focused and disciplined enough to exclude all sentimental subplots, but playful enough to linger for well over a minute on a corridor full of bored killers discretely kicking a paper ball around. His setpieces are characterised as much by stillness as movement, aided by the filmmaker’s unrivalled command of cinematic space.

To’s intimidating efficiency extends to his diamond-sharp characterisations. This is a director who knows the techniques and archetypes of Triad cinema inside out, and he boils them down to a half-parodic essence. These are tough, rational-minded professionals with little time for the mushy male bonding of John Woo’s contemplative criminals.

The loyalty of the film’s five leading men is expressed through pure action as they move from plan to plan in their efforts to suss out the aspiring assassins of boss Lung. Even a punitive beating is nothing to take personally between colleagues who know the rules and know the repercussions for breaking them. It is only in the film’s final 20 minutes that this idealistic image of criminal as businessman is muddied by a narrative turn that curves their loyalties into contradiction, putting business and brotherhood in opposition when they had previously been in tandem.

But more than theme, character or story, The Mission is above all a wondrous exercise in sophisticated cinematic style. Just about every scene could be someone’s favourite, though a special mention has to go to the immaculate centrepiece that is the shopping mall shootout. If Woo is the king of bullet ballet then this mathematically precise display of composure, resourcefulness and intuition makes a case for To as the master of bullet geometry. Call it superficial if you must, but you’d be hard pressed to find a purer distilment of the inherent artistry of the action genre.

1. The Killer (1989, dir. John Woo)

Within a vibrant dreamscape of violent red, angelic white and nocturnal black unfolds a fatalistic thriller of mythological proportions. Religious imagery abounds in John Woo’s most invigorating work of tonal hyperbole, upping the spiritual stakes for a story concerning a guilt-ridden hitman, the cop on his tail, and the blind nightclub singer who brings them both together. It’s a tragic, often nightmarish and always ridiculous work that will push many a viewer beyond their accepted level of suspension of disbelief. But for those open to its stylistic maximalism, this is Woo melodrama at its most crushingly persuasive.

The Killer’s blood-spattered majesty is characterised by Woo’s most volatile blending of the ‘masculine’ and the ‘feminine’, the latter exemplified by such irony-laced touches as a recurring piano pop ballad that provides a dark counterpoint to the mounting carnage. Never again was Chow Yun-fat’s fury so frightening, Woo’s bullet ballet so balletic nor their violence so messily consequential.

John Woo is that rare action filmmaker to actively analyse and deconstruct (if ultimately more-or-less accept) the traditional model of masculinity that so often serves as the moral baseline for the genre. In The Killer, he finds emotional stakes not just in the growing empathy between men on opposite sides of the law and in the tested loyalty between society’s stoic outsiders, but also in the collateral damage they risk causing in their grand conflicts. There are certainly eyebrows to be raised regarding the film’s dependence on female suffering to explore male sensitivity (primarily via the accidental blinding of nightclub singer Jennie). All the same, the method proves effective in providing a distressing moral context for the raging machismo at the heart of this genre.

Woo’s interest in human sight goes beyond the blinding that initiates this tale of redemption. It is a tool of power in sequences of deception and concealment (take the scene of Chow Yun-fat’s hitman spotting a sniper trained on him by following a child’s anxious gaze), but by the time we get to the unholy bloodbath at the film’s climax, we begin to see the logic of Oedipus’ famous act of self-mutilation. Yet as grim and excessive as this film gets, the unflagging passion and proficiency of Woo’s boldly operatic delivery ensures that it is never less than enthralling.