In 1917, a bloody revolution led by the Russian political party of the working class overthrew the long-standing Tsarist monarchy and created the Soviet Union, several combined Eurasian republics with a highly centralized government. The new authority, lead by Vladimir Lenin, championed the rights of workers through strict enforcement, banning of imports, censorship, and pro-communist propaganda. Soviet leaders recognized film for its enormous potential to engage and influence the film-loving, and largely illiterate, public, but could not afford to fund any domestic productions. Nevertheless, film study became a top priority.

Strict Limitations Leading to Big Innovations

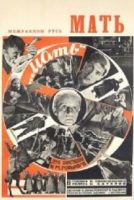

Without many resources, Soviets settled for re-editing pre-revolution films and footage to suit their agenda. Films featured victimized proletarian heroes pitted against a cruel and unsympathetic aristocracy, resulting in a bright and hopeful post-revolutionary future. Many of these films were toured as short documentaries and educational films, to distract civilians from their present hardship and inspire them to rebuild.

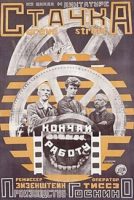

These limitations forced those in the film industry to reconsider editing as a primary tool of persuasion. Opening a filmmaking school in the capital of Moscow in 1919, Soviets encouraged study and experimentation with old and new film techniques in order to optimize the emotional effect of editing. Prior to this, basic continuity editing was in common practice, communicating simultaneous action in different locations, scene changes, or different angles and close ups in a single location. But Soviet filmmakers took it to a whole new level with Soviet Montage. They proved just how drastically the meaning of a film can be manipulated in the editing room. Juxtaposition of thematically similar shots could be combined to intensify a scene, or an overarching meaning, through symbolism. The speed, duration, and rhythm of editing could be combined to create a marked emotional response in the audience.

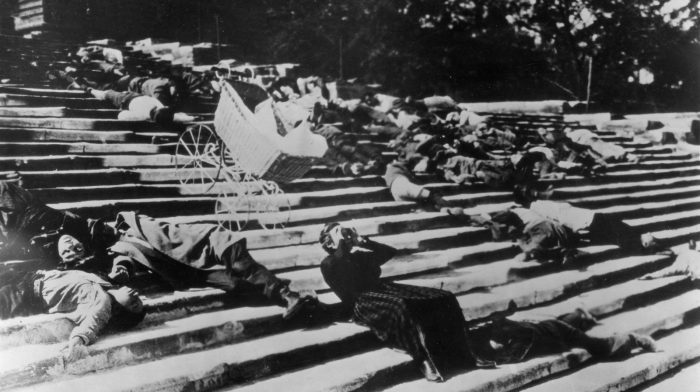

As reconstruction got rolling, so did filmmakers, with globally influential films such as Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin in 1925. The climactic sequence, in which a crowd of Russian citizens get massacred by Tsarist soldiers, features this new dynamic editing while fueling hatred for the former republic. Documentary filmmaker Dziga Vertov’s famous Man With a Movie Camera from 1929 celebrates city life, progress, and the everyday by expanding on the common newsreel, using a self-aware non-narrative style, and playing with a slew of new experimental tricks and effects.

Stalin and the Freezing of Creativity

After Lenin’s death, his successor Joseph Stalin aggressively tightened centralized control, forcing filmmakers away from experimental techniques to the clear, linear, and emotive era of “Socialist Realism“, wherein, under watchful censorship, filmmakers spun heroic tales of Soviet heroes, historical dramas, and romantic parables of the working class meant to be easily accessible and appealing to the masses. Chapaev from 1934, earned global acclaim, telling the story of a revolutionary hero. Musical comedies, like Volga-Volga, also became popular.

At first, the financial support filmmakers enjoyed inspired quality products, but throughout the 30s, the oppressive censorship slowly strangled all creativity out of the process. Filmmakers were treated like the very factory workers they were forced to glorify; as cogs in the propaganda machine, mass reproducing inauthentic formula films. Films went through endless vetting, committees, re-edits, and constant surveillance, and still would end up in the trash. Nothing was safe from ideological scrutiny. Everything needed to have a clear unambiguous message. Stalin even banned the second part of the, now classic, 1944 film Ivan the Terrible, because it depicted the titular character in a negative light, even though Stalin himself commissioned it.

The horrific atrocities Stalin committed during this period resulted in the deaths of millions of innocent people. Filmmakers had more to express than ever, yet more reason to fear expressing it. So few films were created in the Soviet Union after the devastation of WWII that imports, many from the U.S., were readmitted so long as they went through extensive editing, though this may have been more politically detrimental than if they’d loosened domestic control instead.

The Film Industry Thaws Out

Stalin’s death and the subsequent “thaw” loosened the chains of filmmakers anxious to retell Russian war stories on their terms. Both late 50s films The Cranes are Flying and Ballad of a Soldier received global recognition, while exposing the devastation of WWII, and questioning the meaning of glory, honor, and duty. While both films introduced more nuanced characters and deeper questions, they did so under renewed censorship guidelines, which clung to high moral principles while disavowing Stalin and his cherished Socialist Realism.

Throughout the 60s and 70s, foreign art house films were increasingly permitted, and filmmakers returned to the days of experimentation and study, propelled into the weird, philosophical, existential, and poetic, after decades in artistic captivity. While the state-funded industry was artistically liberating, films still needed to be approved by many bureaucratic levels, sometimes pending approval for years. Arguably one of the greatest filmmakers the world has ever known, Andrei Tarkovsky, came out of this period, with cinematic masterpieces like Ivan’s Childhood, Andrei Rublev, Solaris, The Mirror, and Stalker. Due to his token philosophical themes, he was repeatedly barred, blocked, and harassed by the authorities, yet he was also incredibly respected by filmmakers worldwide. Consequently, he was given a lot of artistic freedom, yet allowed to release very few films.

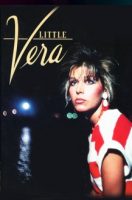

The government further loosened its cultural grip in the 80s, allowing for the depiction of gore, sexuality, drugs, Western culture, and even criticism of Soviet principles. Alienation and disillusionment were increasingly depicted in films like Little Vera and Moscow Doesn’t Believe in Tears. Films like Come and See fully revealed the horrors so many had witnessed in WWII. The Soviet Union was finally dissolved in 1991.

This article comes to us from Tori Galatro, a food and film blogger.