The cinema of Kwon Hayoun is haunted by absence, standing as a ghostly echo of what’s long gone or never was. Though her short films use real-life stories and experiences as their subjects, these elegiac works are astutely aware of the limits of knowledge and memory, crossing legal and physical boundaries into forbidden zones while remaining ever sceptical of film’s ability to capture or recreate reality.

Lack of evidence (2011), for instance, recalls the journey of a Nigerian refugee whose asylum application to France was denied because he had no proof to back up his harrowing tale. In telling this story, the director draws on animation that looks eerily half-finished, constantly drawing attention to its own artifice.

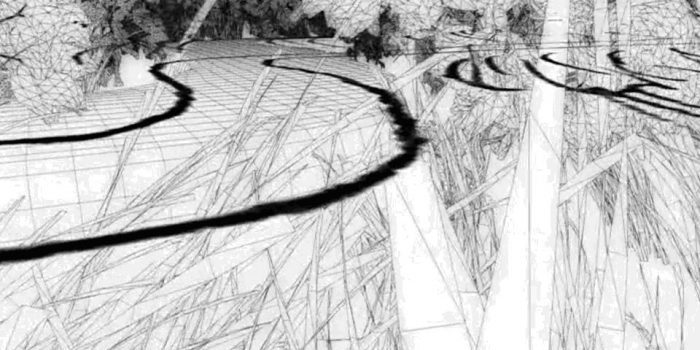

In Pan Mun Jom (2013) and 489 Years (2016), Kwon also uses animation to evoke the strange and unreachable spaces of the Korean Demilitarized Zone, while Model village (2014) fakes a monument to fakery, exploring the propaganda village of Kijong-dong by way of a miniature replica.

With these four shorts screening at the London Korean Film Festival, we spoke to Kwon Hayoun about the nature and intentions of her mesmerising and evocative output.

What was your background in before you came to cinema?

Originally I was studying art at Beaux-Arts in France. I was actually intending to become a painter, and then I discovered photography. I started combining photography with accompanying text, and my projects were about the fleeting moments of life. But then when I exhibited it, I saw that people would look at it again and again and read the text again and again, thereby exhaust it completely. So I felt that I, the artist, didn’t have control over time.

I then thought of video, because video is a medium that includes the time element. So I do a combination of real-life shooting of videos as well as animations. The reason why I moved into animation was because I felt that there were limitations to the real-life shooting of videos. Just because you have a camera in your hands, it doesn’t mean that you can show what you want to show. So I felt that through animation, I could mimic reality in a way that emphasises my point.

Truth is often a slippery, elusive thing in your films. Your animations in particular often make a point of emphasising their own falseness. Do you think that truth is often best expressed in indirect ways, as opposed to trying to recreate reality?

Perhaps the concept of truth or reality is a bit too grandiose for me. My works are more about how I felt it, how I digested it, how I interpret it, because truth or reality can change, it can be in the eye of the viewer. So it’s very subjective. What I can convey is my subjective point of view, and how I felt it and saw it.

Works like Lack of evidence and 489 Years seem built around the memories and experiences of others. Do you see these films as expressing your point of view or theirs?

Maybe I need to explain what I regard a story to be. For me, story is a unique tool, because it’s something that everyone does all the time. You meet someone, you tell them a story, but then by telling and exchanging the story, it somehow creates this common space between the storyteller and the listener. And through listening to a story, you then gain secondary experience of what the storyteller is telling you. So when I meet someone and hear their story, I then digest it. That becomes my secondary experience. So in the end, I am expressing myself.

For example, the fantastical environment in the DMZ, I was never there, but through Mr Kim’s story [in 489 Years] I have reimagined it in my own style. And in terms of the injustices of society that Oscar felt [in Lack of evidence], I have also seen that. I have my personal experience, and I have also gained secondary experience from hearing his story. In the case of Oscar, he comes from Africa, where the culture is not really about what is material. He then comes to Europe, where everything has to be materially proven, physically proven. So that leads to the conflict of different cultures, and that is also something that I felt personally through my experience. And so other people’s stories are a means I use to channel my own experience.

Your films often focus on transitory and intangible things like memory, experience, history and the past. Do you regard your work as preserving these fading things? Can that even be done?

I’m not really a preserver per se. I would never really have thought that my works were designed or intended to preserve things like memory, experience, history and the past. But what is true for me is that my works are about things that don’t currently exist, and the question is always how to get them to exist. Actually, going one step further, that seems to be what preservation is about, although I have never really thought of it that way.

In Model village especially, you acknowledge the cultural influence of propaganda. If you don’t regard your films as outright truth, do you see them as any sort of counter-narrative to the ‘truth’ that’s already out there?

That’s a difficult question. What’s very important to me is the subjective element, because I feel that objectivity is a very difficult concept to realise in the real world. So my focus is really on the story and the time of that story, the people, the protagonists, and the surroundings of that story, and how I can then recreate it. It’s really about the concept of space – the space where I can’t be, where I haven’t visited, somewhere in your memory, somewhere in the past. So I suppose it would be fitting to say that it’s a record of sorts.

For your next project, you’ve mentioned that you’re currently working on something called Bird Ladies.

Bird Ladies stems from another professor that I really respect. She’s now retired, so she’s some years in age, but my work is trying to recreate a part of her memory from when she was twenty-five years old. The idea is to recreate the space that’s in her memory, so that people can actually visit that space.

I suppose you could say that all my works are a sort of experiment. Someone’s actually said that my works are experimenting with the boundaries of memory in terms of where reality starts, where memory starts, whether it’s real or not, and that really rang true with me. So I suppose you could really say it’s like a laboratory where lots of different experiments are happening, where lots of different mediums are being used.

And is this another Korean work?

No, French.

Do you see yourself branching out more internationally in the future?

I don’t know what I’m going to work on in the future, because what’s most important to me in terms of the project I do is what’s important at that moment in time, and obviously that is subject to change.

The one thing that’s very certain is this. I’ve been working with very heavy subjects so far. Each project would take an average of two years, and for the duration of those two years, I would feel a bit weighed down. But my new project Bird Ladies, for the first time, focuses on the beautiful memory of someone, and there is no political message, and it’s almost like a fairy tale.

I’ve actually, for the first time, discovered the joy of working on those positive, pretty subjects, which surprisingly took a lot of courage for me. So that actually served as a lesson for me, and in the future, I want to focus more on beautiful memories, which I think are the best things that any human being can have.